In this issue:

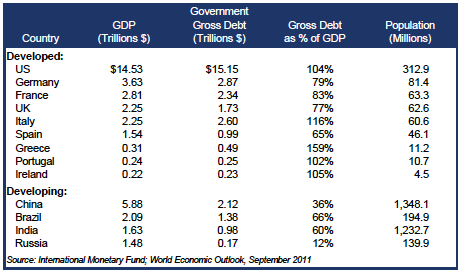

The debt problems of the developed world are once again becoming too big to ignore. The lack of aggregate demand to create growth and the austerity measures to address the deficits are clouding the outlook for continued global recovery and expansion. The austerity proposals are at once too little and too much—too little to meaningfully offset deficits, yet too much to allow for economies to operate at their full potential. Significant divergences continue to exist between the surplus/creditor nations and the deficit/debtor nations which complicate implementation of the structural changes needed to rebalance the global economy. European leaders are struggling to come up with a solution for members’ debt and deficit problems due to the flawed governance structure of the European Union (EU). The United States, with its own well-publicized deficit problems, is in the early stages of an election cycle where ideological approaches have thwarted sensible economic decision making. As highlighted in the table below, government debt levels in the developed economies are already approaching or exceeding 90%of GDP—levels historically associated with reduced growth prospects as taxes are raised and/or fiscal spending reduced to service debt and interest payments:

Selected Country GDP and Government Debt Levels (2011 Estimates)

Across the developed world, several mature economies are already experiencing the highest levels of unemployment in a generation while government balance sheets are straining under excessive debt burdens. This is occurring while the Middle East is dealing with the realities of regime change as it recreates its political and economic systems, and while Japan is rebuilding after its devastating earthquake following a multi-decade economic decline. China is dealing with its own challenges as it takes steps to rebalance its economy in favor of domestic consumption over export growth, including rising inflation and credit concerns in its banking sector. However, China and other developing economies enjoy lower government debt levels, as highlighted on the table above.In the three decades leading up to the financial crisis of 2008,rising debt levels helped to prolong expansions and keep recessions relatively short and shallow. The financial crisis of 2008 derailed credit-fueled growth and ushered in a period of deleveraging during which income is re-allocated from consumption and investment to debt pay-down. In this environment, investors should expect extended periods of slow growth in the developed world, along with increased market volatility. This backdrop creates obvious challenges, but also opportunities. We expect to see increasing pressure on developed economy central banks to monetize debt burdens with printed currency. Certain investments will benefit under such conditions and investors should be positioned accordingly and in advance. We also continue to find world-class companies with exposure to developing markets that are growing. These companies have strong balance sheets and are selling for attractive valuations. While we are mindful that the headwinds discussed above will be with us for several years, our portfolios are positioned to take advantage of the current investment environment by allocating to four key areas:

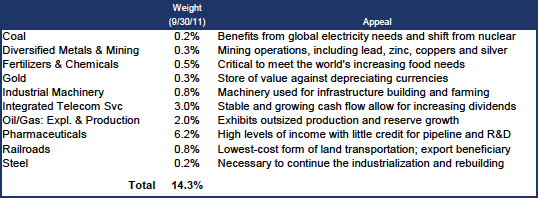

1)“Crown Jewels of the Global Economy”—We continue to emphasize US-based companies that are global leaders producing the goods and services essential to industrialization and rising living standards for the world’s population;

2)Quality Dividend Payers—In response to the Federal Reserve policy to keep rates low and the growing demographic needs of an aging population to generate more income;

3)Gold and Hard Assets—To protect purchasing power during a period of competitive currency devaluations;

4)Cash—Which we will periodically manage to higher levels to take advantage of the shorter cycles and volatility.

For the past three years, our view has been that deleveraging inthe developed world and industrialization and growth in the developing economies would remain the defining features for investment security selection and portfolio management. With most of the developed world in a deleveraging process and with interest rates at or near zero, printing money (the Quantitative Easing or QE we have written about in the past) becomes the primary tool to devalue a currency, reduce the value of debt and stimulate exports. Currency devaluation for one country induces a reaction by others to gain or maintain competitive position. The cumulative effect of this process is to eventually reduce the value of all fiat currencies. Importantly, while there may be periods of temporary dislocation, currency devaluation ultimately tends to raise the nominal value of equities over time, as tangible businesses preserve their respective values within the economy in the face of declining fiat currencies. The four key areas allow us to position portfolios in the beneficiaries of this dynamic environment to protect purchasing power and build capital.

While having a currency union with 17 members with different cultures and policies was perhaps workable when debt-fueled economic growth was strong, the flaws in the Euro structure were exposed when growth was insufficient for periphery members to manage their growing debt burdens. Once part of the EU, uncompetitive economies lost the ability to devalue their respective currencies in response to economic challenges and failed to adjust to the resulting low-growth environments. Unlike the United States, there is no central institution to deal with the crisis nor are the sovereign debts supported by any one country’s credit rating. Instead, the member nations are linked by a single currency (the Euro) and a central bank with the sole mandate of price stability (the ECB). Hence a fundamental contradiction exists between the interests of the stronger nations who want top reserve the wealth they have generated by maintaining a sound currency, and its weaker members with high unemployment who require stimulative policies.Therefore the ECB is left with two choices—to support the deflation-prone nations or to be witness to the EU effectuating the exit of some members. In either case, regaining global competitiveness will require achieving a lower cost structure across much of the region. Unfortunately the EU does not have the luxury of time to address this disequilibrium as deficits continue to rise and debts increase at an accelerating rate from already unsustainable levels.

An essential mismatch between the nations in the north and south became apparent when the growth of the EU could no longer mask the underlying differences in their cost structures. The stronger northern nations, for example Germany and France, have to-date been enormous beneficiaries of the EU as 70% of Germany’s exports involve trade with member countries.

The Germans now have to decide whether to lend support to the weaker nations or abandon them, subjecting the German economy to contracting trade flows within the Eurozone. To support the weaker nations is politically unappealing, but to abandon them would be economically damaging.

In the South, governments control a larger share of the economy and have been extremely generous in providing benefits to government employees with many retiring at 50 years of age and receiving benefits for decades thereafter. These governments have resisted cutting employment and privatizing which in turn now places an excessive burden on their private sectors to absorb the impact of austerity policies. This austerity has led to protests over the perceived unfairness of policies that require lower living standards, personal sacrifice and for the private sector to beara disproportionate burden, while in effect subsidizing government waste and inefficiency. The weak European governments must take the initiative to accelerate privatization to create more dynamic and competitive enterprises while reducing burdens from government budgets. Newly created economic efficiencies, which will ultimately promote growth, result in more unemployment over the short-term and require extensive monetary policy support to smooth the path of debt and deficit management. With interest rates spiking up in the past three weeks, there is little time left for leaders to address the problem, and the ECB and Germany in concert with the IMF and other governments need to act swiftly and decisively.

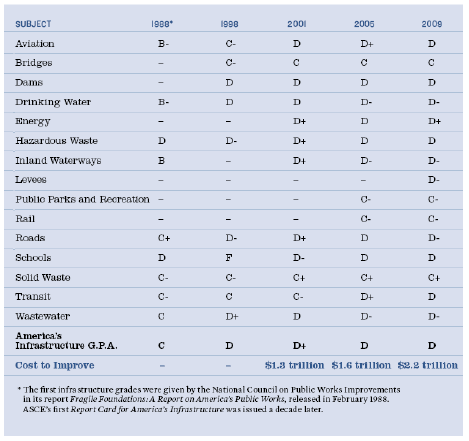

At the August meeting of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC), the committee announced its decision to keep interest rates near zero until the summer of 2013. In October, the committee released its 2014 year-end forecast for unemployment of 6.8% to 7.7% with inflation at or below its target of 2.0%. This suggests to us that the committee may not believe it appropriate to raise interest rates until at least the end of 2014 instead of the middle of 2013. Similar to the global economy, the United States is suffering from a lack of aggregate demand. In order to increase aggregate demand in a deleveraging process for what has been a consumer-driven economy, policy makers will need to see a significant increase in investment to the many neglected areas of the economy including infrastructure. The infrastructure investment requirement is estimated to be in excess of $2 trillion (see table in Appendix), which if undertaken, would contribute to an exciting and positive transformation of the US economy. More important than government investments are private-sector initiatives that could be unleashed by a more pro-growth government policy orientation which could stimulate employment without adding to the US deficits. Approval of the Keystone Pipeline could have been one such example, but at present remains an opportunity delayed.

We are frequently asked when we would expect to see an increase in inflation and a significant improvement in housing. We suggest that there would first need to be solid employment growth for a sustained period, at which point we would also anticipate a reversal of Federal Reserve policy to prevent a significant increase in inflation. A review of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) October Employment Report highlights the challenge ahead for the US and suggests that it could take five to ten years or even longer to achieve an acceptable unemployment rate. As of October, the US had a total of 26.4 million unemployed and underemployed members of the labor force.1The total civilian labor force is 154.2 million and is expanding by an estimated 110,000 new entrants each month. Assuming for the sake of argument that monthly job creation were to increase to 250,000 (or 140,000 net of new labor force entrants), the number of unemployed could be expected to decline by roughly 1.7 million per year. At this pace, and assuming no new recessions, after 10 years the US would be down to approximately 10 million workers still unemployed or underemployed, which would equate to roughly 6% ofthe labor force—a more palatable level. However, realizing average job creation of 250,000 per month will be no easy feat. Over the past three months, the US has averaged only 122,000 new private sector jobs. Currently there are 22.5 million people employed by government on all levels. In the years ahead, it should be expected that some number of these jobs will be eliminated due to budget cuts, which would further add to the ranks of the unemployed.Many of the unemployed will need significant skills retraining to get back into the workforce. With rapid technological advancements and shifts in labor market structure, investment in education needs to be adjusted and increased, unlike our current policy of disinvestment. This speaks to the intellectual bankruptcy of austerity programs without growth initiatives, which will only add to the problem. Clearly, job creation is the central issue for leadership to deal with now and in the future. What is needed now are policies to stimulate private-sector investment combined with near-term government stimulus focused on maximizing returns on any new debts incurred. Any additional near-term deficit increases must be done within the context of a longer-term deficit reduction plan. Examples of private-sector initiatives that would create jobs without costing1 This 26.4 million figure includes 13.9 million members who are unemployed, as well as 12.5 million members who are classified as “underemployed”—including 2.6 million of those deemed to be “marginally attached”to the labor force (defined as those not in the labor force but who wanted and were available for work and had looked for a job in the prior 12 months, but had not worked in the four weeks prior to the survey), 967,000 “discouraged workers”(people not currently looking for work because they believe there are no jobs available) and the 8.9 million who are working part-time but would prefer to be working full-time but could not find full-time employment.

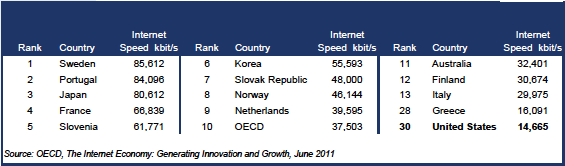

the government a dime would include streamlining of regulations,applications and approval processes for new mineral exploration,production and manufacturing facilities, and a more intelligent immigration policy making it easier for immigrants educated in US universities to remain in the country, start businesses, raise families and buy homes. The US requires an overhaul of the tax code and a rethinking of the entitlement programs. Other policies that would cost the government money but which would likely have a high return on capital include rebuilding the US power grid, investment in infrastructure and job-skills retraining programs. Infrastructure investment in particular benefits from multiplier effects (where each dollar spent creates more than a dollar of GDP) while making the US more competitive.Investment in a smart grid can lower electricity costs and reduce the cost structure of US businesses. Investment in telecom infrastructure can improve productivity. As the table below illustrates, the US internet ranking as measured by download speeds has dropped to #30—below Greece—despite the fact that the internet was invented in America:Global Internet Speed Rankings

As we approach the end of the third quarter earnings reporting cycle, over 70% of businesses have exceeded analysts’ expectations for revenue growth and earnings. Many corporations are raising dividends, continuing share buybacks and providing earnings guidance at healthy levels for 2012. There has been an increase in merger and acquisition announcements for strategic assets. We expect M&A activity to continue, and with each deal,companies are making positive statements about the future prospects for their specific businesses. Moreover a closer look at some of the leading economic indicators suggests that recent easing of inflation may be filtering through and leading to some positive surprises for the US economy, particularly when compared to the low expectations and poor sentiment seen towards the end of the last quarter. In addition, a growing number of global policy initiatives (including currency intervention, and interest rate/tax cuts) are being undertaken in order to stimulate growth to counteract the contraction in many of the developed economies.

In the past decade, the world economies have opened up considerably and today’s drivers of global GDP growth are increasingly the developing economies rather than just the developed ones. Over the last decade, many US investor portfolios that were benchmarked to the S&P 500 were not necessarily well positioned to participate effectively in globalization and the shift from developed to developing economies. The critical industries benefiting from global growth were among the least represented in the index as highlighted in the table below:Globalization is not appropriately reflected in the S&P 500 Weightings

Furthermore we believe that investors need to adjust to an environment of shorter-term economic cycles within the context of longer-term secular trends. With this in mind, there is a virtue to being able to embrace the opportunities that volatility presents to long-term investors. ARS portfolios will continue to adjust the portfolio weightings among the four key areas—the crown jewels of global growth, dividend payers, gold and gold miners and cash—within the context of the secular trends and cycles.We are often asked by clients how one can be invested with all the problems facing an over-leveraged system, namely high unemployment with little or no economic growth in the developed world. In any economic environment there will always be beneficiaries of the prevailing trends, as well as companies and sectors exposed to headwinds. At ARS, the focus is on identifying the important secular trends and determining which undervalued businesses will be the longer-term beneficiaries while avoiding those areas that are most vulnerable. In a period of deleveraging and currency devaluation, capital will flow to those businesses providing the inputs that are essential for the industrialization of the developing economies and the needs of the developed economies. When countries engage in currency devaluation, this process eventually tends to increase the nominal value of gold and gold miners, hard assets and many equities. A number of the businesses involved with the production of these assets are trading today at significant discounts to their net asset values and low multiples of their free cash flows. With interest rates at historic lows and likely to stay there for some years, investors should also look to benefit from the attractive dividends currently available from select US corporations with strong balance sheets and the ability to raise payouts over time. While this Outlook discusses many of the challenges facing the global economy, our investment team is identifying businesses that our research has determined are undervalued and represent attractive longer-term investments to generate capital and protect purchasing power.

Appendix: American Society of Civil Engineers 2009 Report

Sign up to receive The Outlook — our timely newsletter featuring our investment and economic thinking — and highlights from our latest market insights will be emailed directly to your inbox.