| As of 11/10/09 | ||

| Index | Market Value | YTD % Change |

| Dow Jones Industrials | 10,246.97 | 16.8% |

| S&P 500 | 1,093.01 | 21.0% |

| Nasdaq | 2,151.08 | 36.4% |

On October 29th, the US Department of Commerce announced its estimate of annualized 3.5% gross domestic product (GDP) growth for the third quarter of 2009, which represented the first quarter of growth since the second quarter of 2008. Consumption increased as a result of the cash-for-clunkers and first-time home buyer initiatives, yet real disposable personal income decreased. A quarter of positive GDP growth would normally be viewed as positive for the US economy as it signals the likely end of recession. However, the GDP figure masks structural challenges facing the US. Rising consumption on lower incomes is not sustainable. For 30 years, the US has financed above-trend growth through ever-increasing levels of debt. Now this cycle of debt serving as a driver of US GDP growth has come to an end. Consumer savings rates are increasing, consumer credit outstanding is declining, and the result is muted spending and a weaker economy. US unemployment has surpassed 10%, state and local governments are facing crippling budget deficits, taxes are increasing and services are being cut.

Unlike in prior recessions, the US today is not financially capable of playing the leading role in restoring global economic growth. This Outlook focuses on the causes and implications of this important economic transformation. It will be difficult for the US to sustain its recent growth after stimulus spending begins to phase out, and many companies leveraged primarily to the US economy will struggle under these conditions. The Federal Government is now effectively the borrower and spender of last resort, as consumers and businesses are less willing or able to spend, banks are less inclined to lend, and local government budgets are strained. The stage is being set for additional stimulus. However, this comes at a time when the Federal Government is running record deficits, which, when combined with rising debt and the printing of money by the Federal Reserve, is already contributing to the decline of the dollar. The precise timing of further weakening in the US dollar is difficult to predict and there are a number of factors that could cause the dollar to rally for a period of time, as we saw late in 2008. Over the longer-term however, investors should be positioned for the preservation and growth of purchasing power in a weakening dollar environment.

In spite of the challenges confronting the US and other developed economies, developing nations are experiencing strong secular growth resulting in rising living standards for millions of people. We continue to be encouraged by the opportunities for companies with a high percentage of revenues tied to the rapid industrialization of developing markets. Companies that own tangible assets such as precious metals, oil, copper and iron ore should also outperform in this environment, as well as select agriculture and technology companies. Quality businesses with strong balance sheets that pay dividends and are not overly reliant upon the capital markets should also be included in investment portfolios, as well as high-quality, short-term (one to four year) corporate and government bonds.

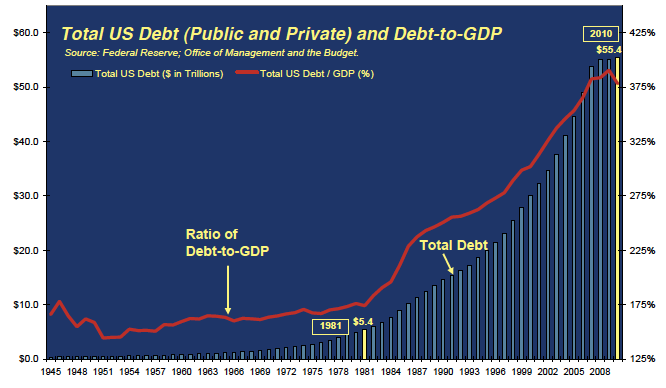

As a percentage of GDP, debt swelled from 178% to 395%-the highest in modern US history, with most of this rise coming from private debt (financial, mortgage and credit card).

Assuming an average rate of 5%, the interest alone on $56 trillion of debt would cost $2.8 trillion per year, or 20% of GDP.

For a while, consistently higher borrowing allowed consumption and capital expenditures to continue rising despite a growing debt-service burden. But the US was effectively required to borrow more each year in order to maintain its growth. An example of this phenomenon was the stimulus provided by mortgage equity withdrawal earlier in this decade. From 2001 to 2006, US consumers withdrew over $2.5 trillion of home mortgage equity for one-time expenditures, providing a nearly 3% annual lift to GDP. Credit card debt also expanded rapidly during this period. However, once home prices began to decline and excess credit availability was no longer available-the fuel driving consumption was gone and all that remained was a higher debt service burden.

Current US Federal Debt as a percent of GDP has reached 84% and is expected to grow to 96% by the end of 2010-a level not seen since World War II. After the war, the US debt burden fell rapidly as the economy grew and spending declined. Today in contrast, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that US debt-to-GDP will grow for the foreseeable future fueled by ongoing deficit spending.

The CBO’s projections call for total new debt issuance of $7 trillion over the next 10 years. The White House Office of Management and Budget, using more conservative assumptions (including that some of the Bush Tax Cuts are extended) projects total deficit spending of $9 trillion over the next 10 years, or $900 billion per year. Rising deficits increase the likelihood that Treasury rates will need to rise in order to continue attracting demand, which could derail the nascent economic recovery by increasing private sector borrowing costs. An additional concern is the cycle that could be ignited by higher government borrowing rates-the average maturity of government debt is at a 26-year low of just 49 months at an average interest rate of 3.4%, well below the average borrowing costs that prevailed over the last 40 years. If debt continues growing as projected and average interest rates were to rise to just 5%, by 2014 annual gross interest expense would approach $1 trillion, or 22% of the annual Federal budget, up from approximately 10% today.

Currency demand is impacted by many factors, including the financial health of the nation issuing the currency. Much of the dollars held by US trading partners are invested in the form of Treasury purchases. If US credit quality or the value of the dollar is perceived to be at risk of further decline, demand for the dollar could continue to fall. The US government depends on foreign buyers for at least one-third of its debt issuance and unfortunately, the US relationship with its foreign lenders is showing signs of strain. This is clear from recent calls by China to move away from the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. These calls are largely just “shots across the bow”, as there is no near-term viable alternative to the dollar as the global reserve currency. However, with the amount of deficit spending needing to be funded through year-end 2010, it is not too early for the US to begin taking the concerns of its lenders seriously.

Although there are pro-growth alternatives for stimulating the economy that might be more supportive of the dollar (such as targeted tax cuts and more liberalized regulatory policies), these proposals are not in sync with the administration’s approach. With unemployment nearing a 30-year high and an election year in 2010, Congress and the administration are understandably reluctant to pursue any policy that would be contractionary and appear willing to risk the ire of foreign lenders in order to continue deficit-funded stimulus spending.

It is important to note that devaluation does not occur in isolation and also leads to a reduction in purchasing power. There is the risk that any benefits will be offset by other countries engaging in competitive devaluations for similar economic purposes. On the other hand, China is facing pressure to appreciate the yuan against the dollar due to its stronger economy, which would be inflationary for imports and result in an effective purchasing power tax on the US populace.

Investors also need to be prepared for the possibility of a double-dip recession in the developed economies, which could be discounted by the stock markets several months before tangible signs of a slowdown emerge. Blue chip, dividend-paying companies with strong balance sheets that are not reliant on capital markets for growth can benefit in a weak economy from opportunistic acquisitions or market share gains, while dividends are increasingly attractive in a low interest rate environment. Balanced accounts should also include high-quality debt with an emphasis on shorter-term maturities (primarily one to four years), allowing for principal to be re-invested at higher rates should interest rates increase in the years ahead.

Sign up to receive The Outlook — our timely newsletter featuring our investment and economic thinking — and highlights from our latest market insights will be emailed directly to your inbox.