Why this is not your parents’ stock and bond market – Part II

In this issue:

“The underlying principles of sound investment should not alter from decade to decade, but the application of these principles must be adapted to significant changes in the financial mechanisms and climate.”

– Benjamin Graham, investor and professor widely acknowledged as the “father of value investing”

We have always viewed the markets as a medium of exchange, swapping dollars for shares of businesses understanding that the opportunity to build long-term capital lies in the discrepancy between the real worth of a business and its stock price as determined by the auction market. Our focus is to own a relatively small number of the best-positioned, best-valued companies in the market, and not the market itself. Investments are made in client portfolios with a view to holding them for the medium to longer-term believing that these companies are the beneficiaries of the secular trends driving the global economy. Before committing capital, our research must produce a clear picture of those investments that are deemed to offer the most cash flow, assets and earnings for the fewest dollars invested. We evaluate a stock the same way we would value the purchase of an entire company. This is the approach we have successfully employed for over 45 years. As more and more market participants make investment decisions based primarily on price and popularity, our decisions continue to be business-driven, based on our judgment of the outlook for the business fundamentals.

While our core principles for investing have not and will not change, the application of those principles must be adapted to changes in the environment as the stock and bond markets today are very different from previous ones. In our April Outlook, we discussed how important convergences in monetary policy, global politics and trade were creating challenging conditions for stock and bond investors. This Outlook will more narrowly focus on some of the key changes that are impacting the structure of the equity market in the United States. These include the significant drop in number of publicly traded companies, the concentration of power of leading corporations, the explosive growth in the number of investment vehicles available and the technological advances such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and high speed trading that are redefining the market’s mechanics and investment approaches. Today’s market is more short-term oriented than ever before. Understanding these changes will enable investors to better navigate the challenges that currently exist and take advantage of opportunities to build and preserve capital. We still believe that many positive factors for U.S. corporations and the U.S. economy continue to be underestimated. In fact, the United States continues to attract significant capital as the currency devaluations that are occurring in the emerging market economies have had the effect of augmenting the attractiveness of the United States economy.

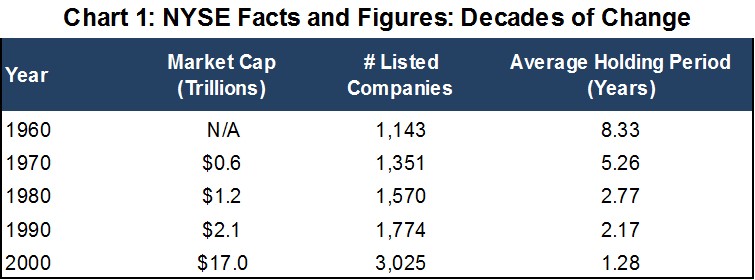

The two most significant changes in the U.S. equity markets are the dramatic drop in the number of publicly-traded companies and the growing concentration in the power of America’s leading companies. These topics were the focus of the recent Jackson Hole Symposium hosted by the Kansas City Federal Reserve. Using the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index (Wilshire 5000) as a proxy for the U.S. equity market, there were roughly 5000 publicly traded stocks in 1974, a figure which peaked at 7562 in 1998 and has declined to about 3492 companies as of December 31, 2017. According to Wilshire, there have not been 5000 stocks in the index since December of 2005. As shown in Chart 1, a historical review of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) confirms a similar pattern with the number of NYSE-listed companies declining to about 2800 as of the end of 2017.

So why has the number of listed companies declined so dramatically? There are two reasons – the low number of newly listed firms and the high number of firms delisting. The lower number of new listings reflects greater opportunity for small businesses to access private capital from either venture capital or private equity investors and the desire for smaller companies to avoid the regulatory burdens of being a publicly-listed company. Bear in mind that private equity firms are sitting with an estimated $1.7 trillion in un-invested capital and continue to raise record amounts of capital. The high number of firms delisting is due, in large part, to the increase in merger and acquisition activity that has been supported by high cash balances at large. corporations, capital repatriation and private equity firm investments supported by the low interest rate policy of the last decade which has made acquisitions highly accretive. In the U.S., there were 5,326 deals in 2017, with a combined value of $1.26 trillion according to a report by Mergermarket. In 2016, there were 5,325 deals, with a combined value of about $1.5 trillion. The United States has accounted for over 40% of global merger and acquisition activity for some time.

“In 1954, the top 60 firms accounted for less than 20% of GDP. Now, just the top 20 firms account for more than 20%.”

–Brookings Institution report by William Galston and Clara Hendrickson

As the number of companies in the public markets has declined over several decades, the concentration of industries has increased. This trend is accelerating as disruptive technologies are affecting companies in all industries. According to a JPMorgan report on global M&A, “technology is creating more differentiation between the largest, most successful firms and the rest of the market, which suggests that disruption is fueling a “winner takes all” environment.” In a working paper by Kathleen Kahle and Rene Stulz titled “Is the U.S. Public Corporation in Trouble?” produced for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the authors highlight that “In 1975, 50 percent of the total earnings of public firms was earned by the 109 top earning firms; by 2015, the top 30 firms earn 50 percent of the total earnings of the U.S. public firms. Even more striking, in untabulated results we find that the earnings of the top 200 firms by earnings exceed the earnings of all listed firms combined in 2015, which means that the combined earnings of the firms not in the top 200 are negative.” Just look at the technology industry today, where Apple and Google operating systems run nearly 99% of all smart phones. Google and Facebook dominate the mobile advertising market, while Amazon, Microsoft and Alphabet dominate the cloud services business. Amazon is expected to capture almost 50% of the U.S. e-commerce market by the end of 2018. While much has been made about the potential for such concentration of power in the hands of a few with respect inflationary pricing, the history of these firms has been to lower prices by disrupting industries. The dominance of these companies can more likely be attributed to their financial strength, their ability and commitment to invest in research and development, and their willingness to reinvent and reinvest for the future. The combination of their dominance and financial strength are reinforcing the competitive positions of these firms as the rich get richer in corporate America.

Concurrent with the changes in the equity markets, market participants now have more choices than ever to participate through a variety of investment vehicles and investment approaches. According to the Investment Company Institute (ICI), the mutual fund industry in 1960 consisted of 161 U.S.-registered funds totaling $17.03 billion. In 2017, there were over 7,956 U.S-registered mutual funds with 25,112 share classes totaling $18.75 trillion.

The number of Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) has grown from around 120 in 2003 to more than 1,700 today. While both are baskets of securities, ETFs added a new element to the equity markets in that mutual funds are only priced daily, whereas ETFs are priced and trade continuously like individual stocks. Furthermore, technology is enabling algorithmic trading that utilizes high-powered computers to buy and sell massive amounts of securities in milliseconds. Consequently, high-frequency trading (HFT) allows traders to move in and out of short-term positions at high volumes and high speeds to capture sometimes a fraction of a cent in profit on every trade. HFT is a type of algorithmic trading characterized by high speeds, high turnover rates and extremely short-term investment horizons. Computer-based trading has become a much larger part of the market’s daily activity and focuses almost exclusively on price movements rather than on business fundamentals. It is estimated that computer-driven trading accounts for 80-90% of trading volume daily.

“The single greatest edge an investor can have is a long-term orientation.”

– Seth Klarman, Founder of Baupost Group and legendary hedge fund investor

While it is difficult to ascertain the average holding period for stocks, the figure has declined considerably as shown in Chart 1. The average holding period for an NYSE stock has dropped from 8.3 years in 1960 to an estimated 1.2 years in 2000, and the number is believed to be even lower today. Holding periods for high-frequency-traded securities have been estimated by some sources to be as low as 11 to 22 seconds. Today more securities are traded based on price movements than are bought and sold based on the fundamentals of the underlying businesses. The growing disconnect between price and fundamentals is creating a greater opportunity for longer-term investors.

While these changes are occurring within the structure of the market, the global economy is in the midst of a period of unprecedented monetary and fiscal policy initiatives, growing economic divergences, challenges to the post-WWII global order, and shifting terms of trade. With a dizzying array of investment choices combined with current global economic, social and political characteristics, people can be easily confused. Investors need to make a few fundamental choices to determine the best plan to meet their specific goals. Investors need to choose between a market approach based upon predicting price or an investment approach based upon the evaluation of business fundamentals and the real worth of each business. We believe it is difficult, if not impossible, to attempt to do both. Business ownership has proven throughout history to be the best approach to building capital, but it requires patience and a longer-term perspective.

“Investment success requires sticking with positions made uncomfortable by their variance with popular opinion.”

– Howard Marks, co-founder of Oaktree Capital, noted institutional investor and author

While more and more market participants are making decisions based primarily on price and popularity, our decisions continue to be business-driven, based on our judgment of the outlook for cash flow and earnings growth. While our core principles for investing will not change, the application of those principles must always take into account changes in the environment. In the past two years, we have generally held higher cash levels to take advantage of the price dislocations due to the realities of today’s market structure. In several strategies, we have reduced the number of securities held, which in part is a reflection of the concentration of power described above, as fewer businesses have been driving the returns of the broader markets. Notably, we have also taken some profits and generated capital gains for clients as the prices of some businesses had been pushed up in the short-term beyond reasonable levels of valuation. Clients should not view trims of a position as a statement on the long-term outlook for that business, but rather as a reflection of our views of over and under valuation. At the same time, businesses at the intersection of important secular trends may experience periods of underperformance and will require some patience in the face of a lack of popularity in the short term. Investors should not confuse popularity, or lack thereof, with the quality of the business or its outlook. A perfect example of this has been the recent price declines of some of our favorite technology holdings where the fundamental outlooks haven’t changed. As a consequence of owning businesses that can fall out of favor for a period of time, client portfolios may underperform the major market indices for some period. Our concern when a business is underperforming is not its short-term popularity, but rather its ability to continue to execute its business plan, grow its cash flows and earnings effectively, and ultimately realize its value.

In addition to the adjustments we are making to our active strategies, we launched the ARS Focused ETF Strategy in March of 2017. This strategy involves our team constructing portfolios that utilize ETFs to express the views put forth in our Outlooks. The strategy is designed to concentrate our investments in ETFs that provide the greatest exposure to our highest-conviction themes, similar to the exposures that we have in our other active strategies. We are excited about this offering as it provides an efficient way to gain the desired exposures, and allows us to manage client portfolios with lower investment minimums.

Those companies that are benefitting from the secular trends we have identified for several years should continue to generate higher cash flows and earnings allowing them to continue to invest to increase their competitive positions, raise dividends and repurchase shares. To this end, we continue to focus on the secular trends favoring technology, health care, energy and defense companies. Smaller capitalization companies should continue to be attractive given their more domestically-oriented businesses in light of the growing challenges in investing in foreign markets. We continue to believe that many positive factors for U.S. corporations and the U.S. economy continue to be underestimated. By implementing the tax cuts and increased deficit spending in advance of the introduction of tariffs, the Administration has, at least in the near term, offset some of the negative consequences of the changing terms of trade. Moreover the devaluations that are occurring in the emerging market economies have the effect of augmenting the attractiveness of the United States economy and it markets. Notwithstanding the changes to the structure of the market, investors should not underestimate the impact of the powerful technological advances coming over the next 36-48 months that will affect every industry.

Published by the ARS Investment Policy Committee:

Brian Barry, Stephen Burke, Sean Lawless, Jared Levin, Michael Schaenen, Andrew Schmeidler, Arnold Schmeidler, P. Ross Taylor.

Sign up to receive The Outlook — our timely newsletter featuring our investment and economic thinking — and highlights from our latest market insights will be emailed directly to your inbox.